Enslaved Ceramists in Alabama

When museums talk about who “made” an object, we are usually referring to the owner of the workshop. In almost all cases, that person was just one among a group of skilled craftspeople who created these objects. Enslaved individuals from the African diaspora were unacknowledged participants in the production of Alabama ceramics. Other potteries represented in this exhibit that might have used the craftsmanship of enslaved persons are the Robert Ussery and Elijah McPherson shops.

|

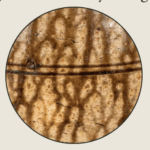

Jug

circa 1850 The shop of Evan Presley (1809-1875), probably an enslaved potter Coosada, Elmore County, Alabama Stoneware with lime-based alkaline glaze Collection of Joey Brackner and Eileen Knott |

Evan Presley’s (1809-1875) family came from Edgefield, South Carolina, an important center of southern stoneware production. One of Presley’s sisters, Meheathlan, was the wife of Abner Landrum (1785-1859), an Edgefield pottery owner who depended on enslaved craftspeople. Presley’s operation in Alabama also used enslaved labor to create alkaline glazed stoneware vessels like this jug. Formerly enslaved potters like Jack and George Pressley continued to work in the area after emancipation. | ||

|

Jar

circa 1850 Shop of Daniel Cribbs (1800-1891), probably an enslaved potter Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, Alabama Salt-glazed stoneware Collection of Ron Countryman and Joe Forbes

|

Migrants from Northern states also relied on skilled enslaved craftspeople in their potteries. Daniel Cribbs (1800-1891) moved from Ohio to Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, where his shop produced salt glazed stoneware like this jar. Harrison and Shepherd were two Black craftspeople who worked in the shop. They were described in an 1851 document as “mechanicks by trade potters.”

After his steamboat exploded in 1845, Cribbs was nearly ruined – he left to follow the gold rush in California. When he returned, he invested in enslaved individuals. Daniel Cribb’s relationship with the South on the eve of the Civil War was a complicated one. They were invested in enslavement, but when he and his son served as enumerators for the 1860 census, and on the last page one of them wrote “faithfull Ohio” – likely a reference to the crisis of union. |